|

|

|

|

~ Karmacharya Study | ~ Tantric

Healing Practices | ~ Rudi Statue | ~

The Chöd Tradition | ~ Project News and Articles

Karmacharya Study

Nityananda Institute Nepal joined forces with the Center for Nepal and Asian Studies of Tribhuvan University on a research project to study the Karmacharyas of Bhaktapur, a caste of tantric priests. Dr. Tirtha Prasad Mishra, the Executive Director of CNAS, assembled a committee of researchers to conduct a seventeen month survey of the Karmacharyas, their practices and history. The research focused on the influence of Karmacharya tantric ritual on the society and culture of Bhaktapur. The study included a survey of extant source materials, including rare ritual texts, as well as field observation and interviews with practicing Karmacharyas.

Nityananda Institute Nepal joined forces with the Center for Nepal and Asian Studies of Tribhuvan University on a research project to study the Karmacharyas of Bhaktapur, a caste of tantric priests. Dr. Tirtha Prasad Mishra, the Executive Director of CNAS, assembled a committee of researchers to conduct a seventeen month survey of the Karmacharyas, their practices and history. The research focused on the influence of Karmacharya tantric ritual on the society and culture of Bhaktapur. The study included a survey of extant source materials, including rare ritual texts, as well as field observation and interviews with practicing Karmacharyas.

The ancient city of Bhaktapur, located eight miles east of Kathmandu, holds great importance in Nepali history. Home to the Newars, the most culturally significant of Nepal’s ethnic groups , Bhaktapur is the source of many of Nepal’s most important religious traditions. For centuries, Bhaktapur served as the Nepalese capital and the seat of the royal palace. Under the rule of the Malla kings from the 12th to the 17th century, Bhaktapur and the Newars developed a flourishing social, political and cultural system.

To ensure the protection and prosperity of the kingdom, the kings of Bhaktapur employed the Karmacharyas to perform elaborate devotional rituals to the local deities. The kings held the Karmacharyas in high esteem for their power and knowledge of goddess-based rituals. Their practices and ritual tradition had a great impact on the social, cultural and political development of Nepal. However, with the fall of the Malla dynasty in the 18th century, the Karmacharyas lost their position in the royal court and their status in society.Today, their role in history is largely forgotten.

The Karmacharyas who remain in Bhaktapur today provide the only living link to the ancient rituals of the Newar. This project provided a means to help preserve this significant tradition and contribute to a deeper understanding of Newari culture.

The research committee consisted of specialists in the field of Asian studies, including Professor Mishra, Swami Chetanananda, Director of Nityananda Institute Nepal and the CNAS Director of Socio-Religious Traditions of Nepal; Professor Alexis Sanderson of Oxford University, Professor T.B. Shrestha of CNAS, and Doctor Purushottam Lochan Shrestha, a historian specializing in Bhaktapur and Newari culture. The committee worked with a prominent Karmacharya, who acted as the liaison between the committee and the Karmacharyas.

The project began in September 2001 with a survey of source materials, including books, articles, inscriptions, chronicles and manuscripts in related topics, as well as relevant unpublished works from the National Archives and numerous other libraries. The final report was issued in September 2003.

Tantric

Healing Practices

In the tantric tradition, practitioners have generally had two goals:

to achieve the state of liberation or moksha, and to acquire power that

could be used for the benefit of others. That power often comes in the

form of siddhis, manifesting in unusual and extraordinary ways. One type

of siddhi that can emerge is the power of healing.

Several strains of tantric healing are practiced in Nepal. Healing practices

have developed among Buddhists, Hindus, and Bönpo groups. There is

also an indigenous shamanistic tradition practiced mostly by villagers

in the eastern and western hills, but its techniques are different from

tantrism.

Tantrism provides a technology for using creative energy or vital force

to effect healing. Healing power, however, does not manifest without careful

cultivation. Tantric healers have generally engaged in extensive sadhana,

which may include a period of ascetic practice. They may perform their

main healing practices in public, but there are also practices done privately,

the details of which are shared only between guru and student. The principal

tools employed in tantric healing in Nepal include mantra, the breath,

pujas (rituals), amulets, and various healing substances, such as blessed

water, rice, incense, ash, and herbal medicine.

Nepal is unusual in its widespread acceptance of tantric healing. For

most Nepalis, access to Western style medical treatment is simply not

possible, and for thousands of years the predominant form of healing has

been spiritual. For westerners, tantric healing methods can be effective

where other forms of treatment are not. Authentic practitioners, however,

are becoming increasingly rare. Swami Chetanananda is seeking to find

such practitioners and do what he can to help preserve these traditions.

One prominent tantric practitioner in Kathamandu is Lama

Tsering Wangdu Rinpoche, whose is known for his ability as a healer.

He is a Tibetan Buddhist of the Nyingma school, and his practices come

from the Zhi-je, or pacification of suffering, tradition of Padampa Sangye.

He is a master of Chöd as well as other healing rituals. Swami Chetanananda

has studied with him for several years, absorbing the essence of his practices

and becoming a lineage holder in his tradition.

Among the other methods of tantric healing that exist in Nepal, there

is one believed to represent the last vestiges of the tradition of Kashmir

Shaivism. Swami Chetanananda is currently studying with accomplished practitioners

of this method and has dedicated himself to learning as much as he can

about their practices.

Rudi

Statue

Nityananda

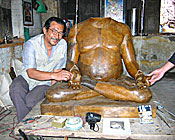

Institute Nepal has commissioned a life-sized statue of Swami

Rudrananda (Rudi) by Nityananda Institute student Karla Refojo and

Ravindra Jyapoo, a well-known Newari

sculptor/bronze caster in Kathmandu. When completed, the statue will be

installed in Nityananda Institute's Portland ashram.

Nityananda

Institute Nepal has commissioned a life-sized statue of Swami

Rudrananda (Rudi) by Nityananda Institute student Karla Refojo and

Ravindra Jyapoo, a well-known Newari

sculptor/bronze caster in Kathmandu. When completed, the statue will be

installed in Nityananda Institute's Portland ashram.

The statue will be cast using the traditional "lost wax" or cire perdu

method used in Nepal for centuries. The traditional process is complicated

and time-consuming, but allows the artisan to achieve very fine detail.

The Newari artisans of Kathmandu are among the best in the world at the

lost wax process. The tradition of metal casting in Nepal dates from the

Licchavi period (300-800 C.E.). The craft had become almost extinct by

the mid-twentieth century, but was revived with the arrival of Tibetan

refugees and the opening of Nepal to tourism, as a new market for the

work developed.

The

conditions in which Newaris work today and the techniques they use are

largely unchanged since the beginning of their tradition.They work in

poorly lit,small spaces with no ventilation, and yet turn out true masterpieces

displaying some of the most refined workmanship in the world.

The

conditions in which Newaris work today and the techniques they use are

largely unchanged since the beginning of their tradition.They work in

poorly lit,small spaces with no ventilation, and yet turn out true masterpieces

displaying some of the most refined workmanship in the world.

Work on the Rudi statue began in Ravindra Jyapoo’s small house at

the base of Swayambunath stupa in 2001. The statue began as a pile of

bricks which constituted the support at the base and the spine of the

statue. Clay, collected from the countryside outside Kathmandu, was brought

to the house and pounded to a smooth consistency, before being handed

over for the sculpture. Ravindra and Karla worked together on the statue

with few, simple tools, spraying the clay continuously with water to protect

it. The summer heat coming from the low tin roof and the wood fire smoke

from the casting ovens behind the house, would have quickly hardened and

baked the clay without it.

After

the sculpture was finished in clay, they needed to create a "die", a relief

copy of the statue made out of plaster. This die is also known as a "mother

mold" that enables the caster to make more than one copy of the statue.

Because this is a very large statue, in order to do this they first divided

the statue up into sections by inserting thin metal dividers into the

clay. These in turn acted as small walls to hold the plaster that was

then brushed onto the surface of the clay. After curing, the plaster sections

were carefully lifted off of the statue, cleaned, and checked for accuracy.

The clay statue was then destroyed, and the clay reconstituted to be used

again in future projects.

After

the sculpture was finished in clay, they needed to create a "die", a relief

copy of the statue made out of plaster. This die is also known as a "mother

mold" that enables the caster to make more than one copy of the statue.

Because this is a very large statue, in order to do this they first divided

the statue up into sections by inserting thin metal dividers into the

clay. These in turn acted as small walls to hold the plaster that was

then brushed onto the surface of the clay. After curing, the plaster sections

were carefully lifted off of the statue, cleaned, and checked for accuracy.

The clay statue was then destroyed, and the clay reconstituted to be used

again in future projects.

The next stage of the lost wax process is the preparation of a wax model,

exactly like the clay one. In order to do this, vegetable oil is brushed

onto the sections of the plaster dye as a resist, and then layers of melted

beeswax approximately one inch thick are brushed over that. The thickness

of the wax is important, since it determines the thickness the metal will

be afterwards. If it is too thin, it will lose strength. If it is too

thick, the cost of the metal is more and will result in a very heavy statue.

After the wax hardens, the wax is carefully pulled out of the plaster

molds, cleaned and checked for inconsistencies, and then joined all together

again into a single unit. When the statue is again in its complete manifestation,

this time in wax, it is thoroughly checked for accuracy in surface texture

and form. In order to cast such a big statue in bronze, the statue must

now be cut again into sections. For a statue of this size, six sections

are used: the head, the torso, the two arms, the legs and then the base.

The wax image is now coated in a slurry of fine yellow clay mixed with

cow dung and dried in the shade. Several layers of clay are applied, and

this process requires great care as it determines the quality of the surface

of the finished statue. The image is then coated with several thick layers

of coarse clay mixed with rice husks. Small openings are left in the clay.

When the mold is completely dry, it is heated in a special brick oven

and the wax flows out of the openings and is collected. The original wax

model, however, is lost.

The statue is then ready for casting. The Rudi statue will be cast using

the five-metal technique. Swami Chetanananda chose the five-metal technique

because it is the method traditionally used in Nepal and India to create

sacred images. This technique combines gold, silver, copper, zinc and

tin, each of which correlate vibrationally to planetary energies, similar

to the way gemstones are used in the Vedic system.

During casting, molten bronze is slowly poured into the mold. The mold

is allowed to cool before it is broken and the bronze statue removed.

Because the mold must be broken to release the statue, each statue made

using this process is one of a kind.

At this time the sections of the statue, now in metal form, are carefully

joined together to form a whole and the surface of the statue is cleaned

with sandpaper and files. The statue is then cold-forged—carefully pounded

with specially shaped dies to take out surface imperfections. The surface

is then polished. In the final stage of casting, the statue is carved

by an engraver with a hammer and special chisels to etch out the final

details. The statue is now ready for a patina, to add the depth and tone

of color desired. The Rudi statue will have a bronze, copper toned body

with an antique gold finish worn away over it, reproducing a 14th century

patina.

The Rudi statue was completed in the spring of 2006. Karla Refojo has

published an article about her experiences at asianart.com.

There's a short

article about the statue's arrival in Portland at the main Nityananda

Institute website.

The

Chöd Tradition

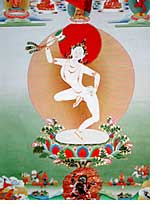

Chöd

is an ancient cremation ground practice of Indian Buddhist origin. It

is probably as old as Buddhism itself. According to scholars, Chöd has

never been a unified school of practice. Instead, it has various lineages

and traditions. One of the foremost practitioners of Chöd, Machig Labdroön

(1062—1153 C.E.), tailored the practice of Chöd to the particular

needs of her students, giving them different meditations that led to separate

lineages.

Chöd

is an ancient cremation ground practice of Indian Buddhist origin. It

is probably as old as Buddhism itself. According to scholars, Chöd has

never been a unified school of practice. Instead, it has various lineages

and traditions. One of the foremost practitioners of Chöd, Machig Labdroön

(1062—1153 C.E.), tailored the practice of Chöd to the particular

needs of her students, giving them different meditations that led to separate

lineages.

During a visit to Nepal in 1997, Swami Chetanananda encountered one of

the greatest living practitioners of Chöd, Lama

Tsering Wangdu Rinpoche. They both describe their first encounter

as a meeting of two currents. In the next year, Lama Wangdu shared his

practice with Swamiji and made him a lineage holder in the Jigme Lingpa

Chöd tradition.

The Chöd ritual is traditionally performed after dark in cremation grounds

or disturbed places. In the course of the practice, practitioners visualize

making an offering of their own bodies, which are cut up, transformed

into nectar, and distributed to various classes of guests who are called

to participate. The guests include spirits and negative energies that

cause harm and disease. After consuming the feast prepared for them, these

spirits are satisfied and subdued.

Chöd brings benefit to the total environment, including the practitioner.

The ritual involves a total sacrifice of everything identified as ourselves,

but it in no way diminishes us—it only makes us bigger. This understanding

is essential to authentic spiritual practice. As Swami Chetanananda says,

"Chöd is the ancient underpinning of all ritual practices."

Chöd has become a part of the programs offered at Nityananda Institute.

Hundreds of Institute students have received initiation in Chöd practice

from Lama Wangdu. Many of them have been practicing for several years.

Most of the students visiting Nepal have had the opportunity to see Lama

Wangdu practice Chöd at one of the main cremation sites or Vajrayogini

temples in the Kathmandu Valley.

This spring Nityananda Institute received a $5,000 grant to produce a

documentary about the art and iconography of Chöd. The project is called

"Art of the Chöd" and will focus on the imagery and ritual implements

used in the practice, using both old and modern examples. The film will

explain and de-mystify the powerful symbolism of Chöd for those unacquainted

with the practice. It will be the first documentary ever produced by the

Institute.

The idea for the film arose because the imagery associated with Chöd is

graphic and the deities invoked can appear menacing to the uninitiated,

who are not aware of the purpose of the practice. By explaining the purpose

of the ritual, the documentary will promote understanding of these images

and the nature of the practice among a wider audience.

The documentary will be produced in DVD format and will feature footage

of Lama Wangdu performing the practice, passages from the text practiced

at the Institute and Lama Wangdu’s and Swamiji’s commentary,

and paintings, sculpture and ritual implements from public and private

collections, including collections of students at Nityananda Institute.

.

This project is the first step toward another, longer film the Institute

would like to produce—a documentary about Lama Wangdu’s life

and practice.